About two years ago, I moved into a gated society for the first time. Until then, I’d lived in an independent house (as a kid), a standalone apartment (as a bachelor), and then in independent floors and government quarters after marriage. So, I was genuinely excited about living in a well-run micro-community.

Two years later, while that initial excitement hasn’t completely worn off – my office is a stone’s throw away, festivals feel more festive, and there are amenities (that I am yet to use), a quiet frustration has crept in. The kind of frustration familiar to any honest, tax-paying citizen dealing with bureaucracy. I’ve come to realize that gated communities are mini-republics, mimicking the politics, power dynamics, and apathy of the larger nation in every way. And I’m clearly not alone, lunch table conversations at office have revealed that this is true for almost every gated community.

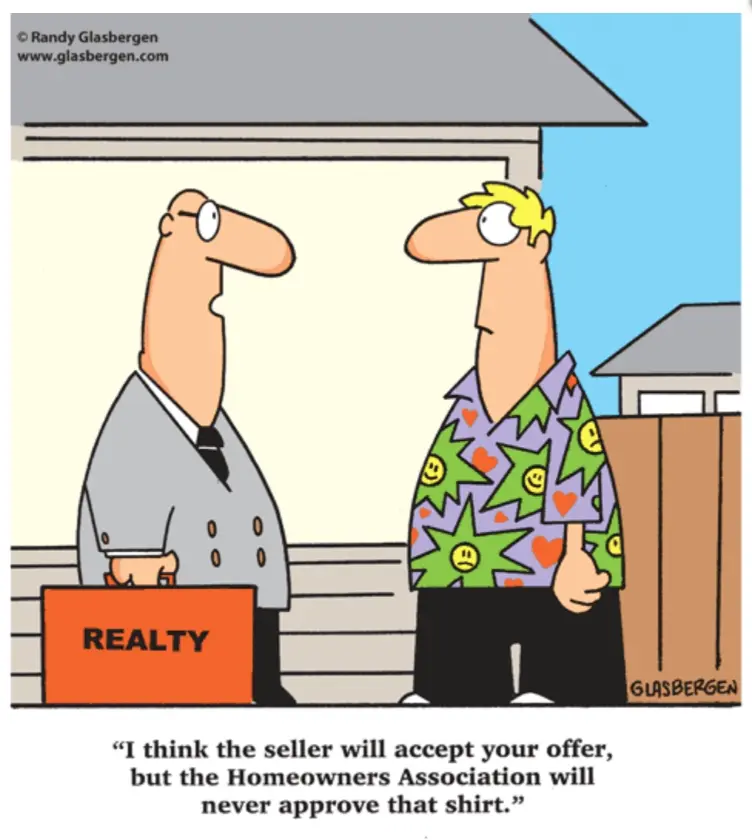

Take the rules. Not the reasonable ones about parking or noise, but arbitrary decisions, which are often a knee-jerk reaction to a one-off incident, or sometimes to no incident at all.

Consider a common scenario. One day, a new rule appears out of nowhere, say, late-night food deliveries are suddenly banned. There’s no announcement, no discussion. Residents only discover the change when they’re called down to the main gate at 1 AM to collect a cold dinner. There is an immediate outrage on Whatsapp group, angry emojis fly, and for a brief moment it feels like a digital protest is underway.

Then someone posts about a totally unrelated topic – a stray cat stuck on a terrace in a neighboring society – and the conversation shifts. The outrage disappears. And just like that the digital protest dies.

In all this, the association often remains silent. They don’t need to engage. They understand something fundamental, which many politicians have mastered, and naive citizens are yet to figure out: silence works. Don’t respond, don’t engage. People will rant for a day and then move on.

And we do.

At first, I was annoyed by these opaque decisions that made no sense. But more than that I was really intrigued by the lack of the residents’ reaction.

People living in these gated communities are usually well-educated professionals, the kind you’d expect to demand accountability. Yet, when faced with irrational policies at home, only a few speak up, while most shrug and move on. Some because it doesn’t affect them. Others because they’d rather not get involved. Many because they assume someone else will.

It’s a frustratingly common attitude. I used to think it is just apathy or selfishness, until one day, while reading an article (I don’t remember which one), I came across a concept in social psychology called the “Collective Action Problem” that helped explain it better.

When the perceived benefit of action is concentrated among a small group, and the cost of action is spread out among a large group, the smaller group tends to organize more effectively. The larger group, even if collectively harmed, finds it harder to mobilize. It feels like too much effort for too little personal gain.

You can see it everywhere. I remember years ago in Gurgaon a group organized a massive protest for a cause important only to them. The roads were jammed, the city came to a standstill, and the protest was a success. As I sat stuck in traffic, I remember thinking that those few who had something to gain were out on the streets, fighting for it. Those who had something to lose stayed silent. Why didn’t they speak up?

Now I think I know why. That’s the collective action problem in action.

It’s the same with gated communities. A few end up making the rules, while the rest remain disengaged.

And this isn’t a uniquely Indian problem.

Apartment boards and housing associations across the world behave the same way. Fredrik Backman captured it brilliantly in his short story “The Answer is No”. In a seemingly normal Swedish building, Lucas’s life turns upside down when residents’ board launches a full-scale investigation into who left an old frying pan on the ground.

“We’ve taken a vote and decided that you should be the president of the Pile Committee. Because you seem to have good ideas,” says Head One.

“Good ideas?” Lucas repeats.

“You came up with the idea that anyone who has a new frying pan should be a suspect!” says Head Two.

“I didn’t actually,” Lucas attempts to clarify but is interrupted by Head One.

“So now you’re the president of the Pile Committee! Congratulations! You can’t change the name of the committee because it took a whole extra meeting just to decide on it!”

“I absolutely do not want to . . .” Lucas starts but doesn’t get any further before Head One declares: “It’s already decided! If you didn’t want to be elected president, you should have come to the meeting. Those are the rules!”

Absurd, but oddly familiar. Whether it’s a gated society in Gurgaon or a co-op in Stockholm, the script often reads the same.

The housing committees sooner or later become micro-governments. They levy taxes (maintenance fees), draft laws (bylaws), manage public works (gardens, lights, water tanks), and enforce order (security and fines). And like most governments, they come with the usual challenges: overreach, limited transparency, and the quiet hope that residents won’t question too much.

Ironically, the most law-abiding residents are often the most frustrated. They follow the rules, pay their dues, and expect transparency. But when they raise concerns, they’re brushed off. Meanwhile, those who bend the rules face little consequence.

No one sets out to build an unfair system. But when rules are made by a few and tolerated by the many, that’s often where we land.

So what does fair governance even look like?

The philosopher John Rawls offered an elegant solution: the “Veil of Ignorance”. When designing rules, imagine you don’t know your place in society. You don’t know if you will be rich or poor, owner or tenant, association member or resident, a young bachelor or a married couple. Would you still support that rule? Would you still ban late-night food deliveries if you don’t know whether you would order food every night at 1 AM?

It’s a test very few societies would pass.

But perhaps that’s the point. A gated community isn’t just a collection of buildings. It’s a mirror reflecting our relationship with power, our willingness to speak up (or stay silent), and our tendency to look away when something doesn’t directly affect us.

We get the governance we tolerate – in the country, in the state, and even in the housing society.

Thanks for reading! I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below. If you found this useful, please share it with anyone who might benefit from it.

Want to stay in the loop?

To get notified when I publish my next article, you can subscribe to my newsletter here. I send an email every few weeks when I publish something new – just links to articles I’ve written, and occasionally, books or articles I found worth reading.

Photo Credit: